Comments to "Whither Peer Production"

“Then Peer Production sat down and wept, because there were not other worlds for her to conquer”

Gnu-Linux and Wikipedia. Two triumphs of peer production. Wonderful. What next?

</em></u>

Benjamin Mako Hill asked me some feedback about his really interesting Libreplanet 2018 Keynote on “How markets coopted free software’s most powerful weapon”, and with painful delay, here it is.

For readability, here I have synthesized and rearranged the parts of that talk on which I had something to say, as if they were a single dialogue between Benjamin and me. Any error in this synthesis is obviously mine. But you should really check out by yourself both the talk video or here, and the slides and transcript/notes.

Of Airbnb vs Couchsurfing, and what it means

Mako: Couchsurfing is a cooperative, a Commons, in which by statute there cannot be exchange of money. Airbnb, instead, is a market, deliberately built to exchange/make money. [I assume that] most people hosting on Airbnb would never have hosted people for free on a site like Couch-surfing.

Marco: No surprise here. Marriott Hotels have the guts to say that they are “entering homesharing”, but even they would never dream to offer themselves for couchsurfing. If one’s motivation is money, couchsurfing simply doesn’t exist.

Mako: Airbnb put to market techniques developed on couchsurfing by the Couchsurfing community. It is an example of how a non-commons-based producer has learned from commons-based ones in ways that allow them to get many of the benefits of working in a commons without actually providing goods or services that are freely shared, or free as free beer. With those benefits, plus all the benefits that markets bring, the non-commons-based producer is increasingly beating the commons:

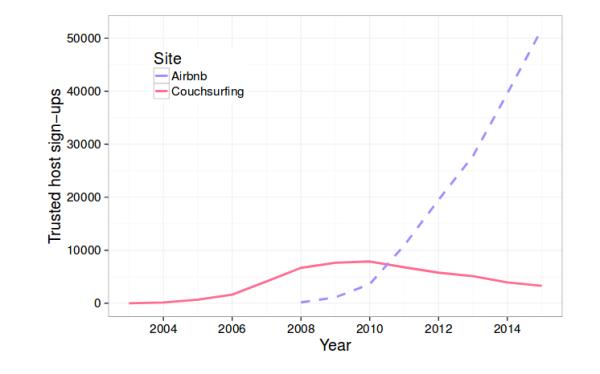

From the slides: Trusted hosts on Couchsurfing and Airbnb 2002-2015.

</em></u>

Marco: Airbnb surely learned a lot from Couchsurfing, but maybe what is happening here, or in any case what really matters, is something else. I have a very strong feeling that, in any field, whenever something like Airbnb becomes technically possible and economically sustainable, never mind profitable, it will surely have many more users than a Couchsurfing-like alternative.

And I also feel that we should not be surprised at all, or sad, about this. Maybe what is happening is that “couchsurfing compatibility” has a built-in limit, which is exactly the same built-in limit to usage or contribution to Free Software in GNU/FSF fashion.

And that limit is the trivial fact that, just like (very) few humans are born brainwired to be good doctors, even people with the genetic attitude, not just the couch, to engage in couchsurfing are a minority. One that, no matter what we do, will remain smaller than that of people able and/or willing to engage only in Airbnb-style “exchanges”.

As for the trusted hosts trends, here is an hypothesis, without any pretense of authority: maybe one of the main reasons for those trends has nothing to do at all with how many people like cooperatives and community, or how much Airbnb learned from whom. Maybe one reason is simply The Great Anniversary Of The Mnth. That is, with just one or two years of unavoidable hysteresis, the 2008 meltdown. Maybe that chart simply says that:

- Unless one can afford months or years of travel, traveling cannot be free. And if one can’t afford a plane ticket to get somewhere, it doesn’t matter how much couchsurfing she could get there for free.

- starting in 2008, lots of people from all ages and income brackets found themselves with much less money than before

- among those people:

- those who, before 2008, could only afford couchsurfing, after the crash had no money anymore to reach most couches, see above

- those who until then had had a couch to spare lost it to being forced to sub-rent, move back with their parents, or move to a smaller apartment

- many of those left with just less money than before, but a spare room or whole house, were “forced” to start monetizing it, simply to keep paying their mortgages, nice colleges for their kids and so on

- many people who after 2008 could still afford to travel but, before 2008, would have only considered 3+ star hotels for their holidays, had to fall back on cheaper, but still “trendy” solutions as “homesharing”

In other words, maybe the 2008 meltdown made the couchsurfing tribe just enough poorer to make their capability to share or reach many couches disappear. And the same event also forced a distinct tribe to be born and to accept Airbnb. Airbnb just came in at the right time for those people.

Another natural reason for those trends, which has nothing to do with human nature, evil market geniuses and so on is mere aging. If I’m not mistaken, both Airbnb and CouchSurfing are mostly first-world communities, i.e. made of people from aging countries. What you like or accept as a student is not what you prefer when you are 30+ years old.

Mako: Fabio Landini created a [model of cultural subsidies that shows how working openly and providing users with freedom can be at least as good a way of building software as working without it.

Marco: OK. But if it is a model that, simply as a consequence of human nature as said above, is genetically compatible with many less people than other models, the end result does not change. At least if we keep trying to push that cart from the wrong side (more on this below).

On matured fields, and markets learning from peer production

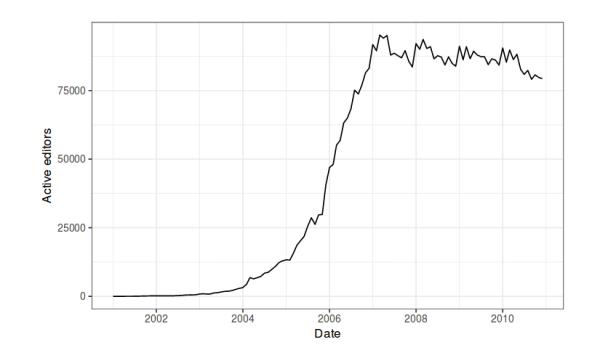

From the slides: Wikipedia active editors, 2000-2012.

</em></u>

Mako: Peer production has exited a period of meteoric growth. Wikipedia is still the 5th most popular website in the world [but its active editors have not increased for years]. We are simply not adding new successful cases the way were 15 years ago. And while we have matured as a movement, our opponents have found ways to benefit from the kind of mass collaboration that used to be something that only we could do (best example: the Apple app store).

Marco: as I see it, in general this may just be the same general issue I already mentioned. While it is absolutely true that someone found a way to exploit mass collaboration in this space (we may even say that it is humankind’s history in one sentence, since dawn of time), framing the landscape in that way may be misleading. Maybe what those graph show is, again, simply that:

- genetics-wise, mass collaboration with the GNU/FSF style and approach is inherently feasible and worthwhile only to a very small percentage of people.

- hard economics realities make collaboration, in many case, a luxury. See next paragraphs

While we are at this… speaking of Wikipedia:

- today, active contributors must a) have broadband and b) be “rich” enough to afford editing (but above all: “edit wars”!) for free. Today, the overwhelming majority of people with that profile are in demographically declining countries, if not only in the (relatively!) richer areas of those same countries. “People elsewhere can’t afford editing Wikipedia”. Edit wars alone are the reason why even people like me never contributed to Wikipedia, and probably never will. So I suggest that we should not be surprised, or worried, or look for complex models, if the number of active editors stopped growing

- Wikipedia does need to keep growing (in the right way: quality and diversity, before volume). Therefore, Wikipedia does need many more editors, and above all much more diversity among editors than today. No question about it. At the same time, in my opinion, rushing to bring many more editors to Wikipedia can have unintended, but not unpredictable consequences that we may not like. Let’s do it right, not quick, please.

- Wikipedia is so important that it must be a thousand times more cautious than almost everybody else, before accepting money. Proposals like this really worry me. *Wikipedia is useful. The way almost everybody who writes online uses Wikipedia is consistently bad. People who link to Wikipedia just out of lazyness, when there are pristine sources, just contribute to make those sources less visible in search results. Not good.

Back to peer production

Mako: The vast majority of free software projects. The vast majority of wikis. The vast majority of information commons online—even successful ones we all rely on are not peer production because they’re not collaborative! We don’t need peer production to create real value.

Marco: Right. We need to convince everybody else to fund the few who do create real value, collaboratively or not.

Mako: In the very best case, we’ve got to come to terms with the fact that our opponents now have the power of online distributed collaborative production too.

Marco: I would suggest that we have to come to terms with the fact that, in the big picture, software (or more exactly: saving the world starting or focusing on software) is much less important than what the GNU Manifesto says. I believe that the standard way to advocate Free Software and related “digital freedom” reached a communication plateau ten, probably 20 years ago. In and by itself, I do not think insisting with that approach and style will achieve anything crucial in time, i.e. in the next 1/2 decades.

Where to go from here

Mako: I suggest that:

- Advocacy [should become] focused on reaching end users not companies

- Working with government and engaging in lobbying

- Supporting change through civil-society organizations, non-profits, and activism

- learn from groups fighting for other public goods like the environment, public infrastructure, public broadcasting, etc.

Marco: On point 1, I couldn’t agree more. See this piece of mine from 2008.

Ditto for point 2, as long as working and lobbying is focused on promoting really open, free-as-in-freedom formats and protocols before code. As examples as what I mean here, see this rant of mine from 2001 or this seminar from 2005.

Finally, about points 3 and 4: rather than merely learning from certain groups, the only next step may be to join the same groups. For example, by far the biggest problems with Airbnb, if not the only ones that matter in the big picture and 90% of people can relate about, are gentrification, and in some cases tax evasion. Not that Airbnb is not running on Free Software, or not creating a Commons. The only problem with Apple and the Apple store that matters to that ~95% of humanity not genetically brainwired to love Free Software is not that Apple mastered strategic closedness instead of the strategic openness: it is tax evasion, and the pollution caused by manufacturing, and locking-in thanks to closed HW/SWdesign, stuff that it is impossible to repair.

Conclusion: let’s work more on this

All my comments above come from 20+ years of using Free Software, writing about it and related freedoms, and closely observing the corresponding communities. None of those conclusion is definitely set in stone. But one thing I am sure about is that the more we study this field taking into accounts those issues, the better it is, and if I can contribute also by joining some project, just contact me.

(initial quote of Alexander the Great courtesy of Plutarch and/or Hans Gruber from “Die Hard”)

Who writes this, why, and how to help

I am Marco Fioretti, tech writer and aspiring polymath doing human-digital research and popularization.

I do it because YOUR civil rights and the quality of YOUR life depend every year more on how software is used AROUND you.

To this end, I have already shared more than a million words on this blog, without any paywall or user tracking, and am sharing the next million through a newsletter, also without any paywall.

The more direct support I get, the more I can continue to inform for free parents, teachers, decision makers, and everybody else who should know more stuff like this. You can support me with paid subscriptions to my newsletter, donations via PayPal (mfioretti@nexaima.net) or LiberaPay, or in any of the other ways listed here.THANKS for your support!