Even the blockchain can be imperialist

Of course. Why not?

What is the blockchain, again?

The simplest possible definition of blockchain could be that it is a technology to create distributed public databases, not controlled by any single entity, and can record data of whatever kind in ways that make it impossible to alter it, once they have been inserted in the blockchain itself.

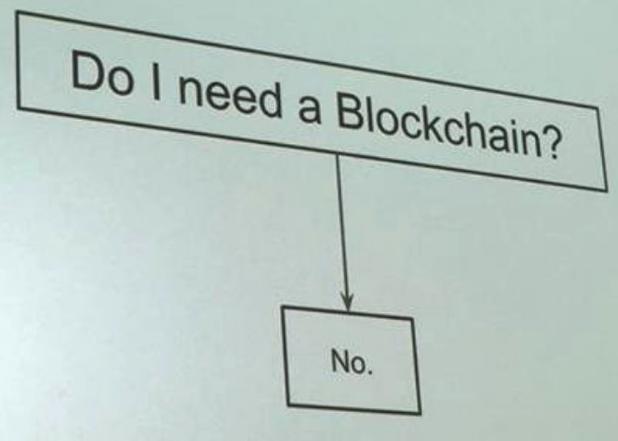

The blockchain suffers the same problems of almost any other “new” digital technology from the Internet of Things to 5G networks or driverless cars: too many blockchain applications, or “disruption”, are overhyped solution in search of a problem, as exemplified by this popular internet meme:

Jokes and memes aside, of course the blockchain, like any other technology, can have concrete, positive uses, that we must discover and test. But for the same reason it is important to be aware of the potential unintended consequences of pushing blockchains everywhere, for every problem.

About one week ago Olivier Jutel published an intriguing paper that can help reflect on those consequences, titled “Blockchain imperialism in the Pacific”. Since it is over 8000 words long, here is 500-word synthesis to help everybody see what the problem is, and why read the full paper.

The Pacific Ideology: blockchain as analogous to indigenous cultures and authentic mediation

Blockchain proposes a participatory notion of data encryption to unify and mediate economic, social and political life.

In developing countries, blockchain-based solutions and aid projects can exploit regulatory weakness, leveraging a desire for tech-development.

The same countries thus become key testing grounds for blockchain governance solutions, to manage and map material resources outside the control of largely corrupted states.

Instead of empowerment, this drive can create new ways to accumulate and exploit data about the same communities, and new dependencies from foreign technological infrastructures that cannot be replicated locally.

Examples in the Pacific area include blockchain-controlled supply-chains for tuna fish, financial innovation in humanitarian relief and projects to manage with a blockchain the property rights of indigenous Fijian lands.

A tuna fish blockchain in Fiji (which is the same I criticised three years ago) “intensifies extractive regimes of export-led growth, represents a cost born by Fijian fleets and allows the potential platform monopolization of supply-chain data." Besides, merely tracking fish with blockchain does very little to make Fijans able to buy their own fish, or Fijan companies to compete with much bigger Chinese ones.

In Papua New Guinea (PNG) a 2018 proposal would obligate the government to establish a blockchain special economic zone (SEZ), hosting a centre for global financial services. The same project would also “empower” with the blockchain indigenous economic practices: “alternative economies and governance systems are deeply ingrained in our culture and are still alive and well, and blockchain allows us, for the first time, to capture this activity”.

Oxfam’s Unblocked Cash project sought to utilize blockchain systems for rapid cash-based disaster aid in parts of Vanuatu that are highly vulnerable to extreme weather and geophysical events. According to the paper:

- the project failed by its own admission to embody blockchain governance objectives of transparency and disintermediation. It is controlled by a for-profit developer, and most participants cannot access, or understand the information stored on the network.

- it is not self-evident what virtues blockchain might have over mobile telephony payment systems that match existing financial regulations and communications infrastructure

In Fiji, 90% of land in Fiji is owned by indigenous (iTaukei) communal groups and administered by the government’s iTaukei Land Trust Board (TLTB). In 2019, some American and Japanese companies have proposed a blockchain prototype to manage leasing and registration of those lands. In that system, blockchain linked SMS messaging would be “the ultimate decision-making mechanism to manage and bring communal lands to market”.

The problem is that, historically, TLTB is a direct result of “human resistance to colonial expropriation” performed through foreign surveyors working to “define and register all native lands… to delineate properties that could be bought and sold”. According to the paper, TLTB is based on mutable, hard to code usage, traditions and records. It is, that is, incompatible by definition with the immutability that is the core of any blockchain.

The conclusion? Cases like these make of blockchains “a means of maintaining and extending bureaucratic and commercial power”.

Who writes this, why, and how to help

I am Marco Fioretti, tech writer and aspiring polymath doing human-digital research and popularization.

I do it because YOUR civil rights and the quality of YOUR life depend every year more on how software is used AROUND you.

To this end, I have already shared more than a million words on this blog, without any paywall or user tracking, and am sharing the next million through a newsletter, also without any paywall.

The more direct support I get, the more I can continue to inform for free parents, teachers, decision makers, and everybody else who should know more stuff like this. You can support me with paid subscriptions to my newsletter, donations via PayPal (mfioretti@nexaima.net) or LiberaPay, or in any of the other ways listed here.THANKS for your support!