Gerrymandering 2.0 is built right into your social networks

There’s more online to gaslight you than mere echo chambers and filter bubbles.

“Filter bubbles” and “echo chambers” are a structural flaw of today’s social networks: if users are shown only an algorithmically curated and biased subset of “news” or comment about some issue, eventually they believe that that is the only and whole truth on the matter. And vote accordingly.

A “previously unrecognized obstacle” to informed democracy

A recent paper describes a related, but distinct, way in which today’s social networks can affect voting behaviour: the mere sets of users connections can sway votes or public opinion. Even when the involved parties on same issue, be it world trade or abortion, have equal sizes and influence. All is needed is that a small number of influencers is connected to the right mix of other users.

Another consequence discussed in the paper is that politics can end up in deadlock, that is no way to reach any consensus on some topic (Brexit, anyone?), simply because the engaged parties are connected to each other in the wrong way by their social networks.

“Previously unrecognized obstacles” to informed democracy

The problem is that in politics, as in many other fields of life, “avoiding gridlock requires information about how others will vote”. But when social networks become primary sources of information, the mere procedures with which they make people create their list of contacts may shift enough individual “voting strategies” to make a difference.

Information gerrymandering

What the paper shows is exactly how connections among users can be set up in ways that lead some individuals to reach misleading conclusions about the preferences of the whole community they belong to. In other words, your set of visible connections can influence what you believe about everybody’s voting intentions, and this of course can alter the outcome of an election.

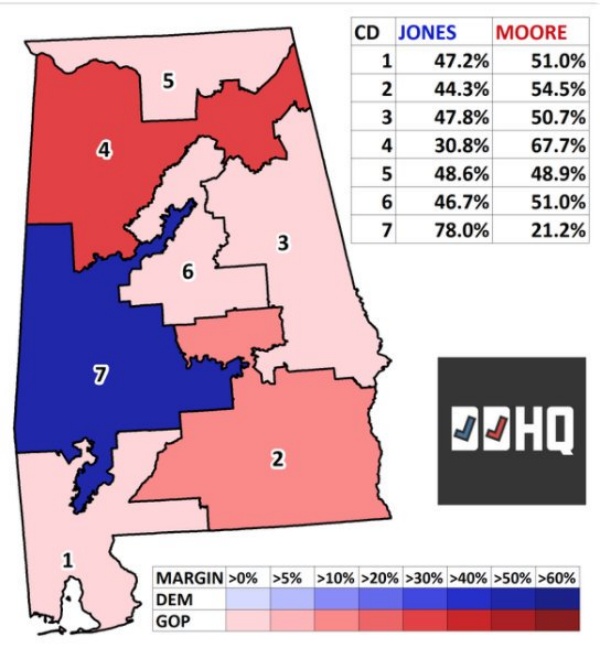

Traditional gerrymandering alters “proportional representation in a democracy” by “connecting” voters, that is grouping them in electoral districts, in ways that make one specific group the majority one in each of those district. Here is a real life example from the US:

How to win 6 of 7 seats with a MINORITY of votes

</em></u>

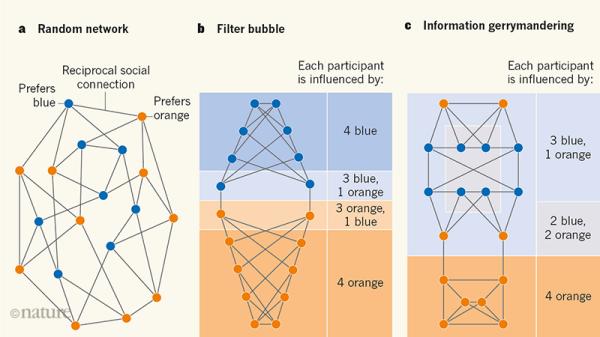

Information gerrymandering, instead, is what happens when the same effect is obtained by distributing connections among users. The users, for example, may be induced to connect in ways that the members of one group “waste their influence on [already] like-minded individuals”, as shown in this example:

Here, two-thirds of voters mistakenly infer that blue is more popular, simply because “orange” voters are connected to other users in ways that make them believe that the majority of people is with the “blue” party.

Could information gerrymandering actually alter real elections?

Probably yes, but how likely is it? The paper acknowledges that this is not clear yet, but points out that information gerrymandering may still influence other collective decisions as crucial as voting, in the long run: company boardooms, juries and parliaments are all communities whose votes may be influenced in this way.

Even in elections, people are more likely to vote in elections that they believe to be close contests. If a social network make only certain groups believe that the contest is close (or isn’t), this will encourage certain groups of citizens to vote, or abstain, more than others, which of course will alter the final result.

The final recommendation of the paper, and my own one

The paper concludes reminding that:

- social-network websites deploy technologies that restructure social connections by design.

- information gerrymandering might arise without conscious intent, but simply as an unintended consequence of machine-learning algorithms that are trained to optimize user experience

And therefore concludes that “social-media ecosystem is overdue” for regulation on these matters. My solution? Make the “social media ecosystem” of today obsolete and make any of their replacements slow, of course.

Who writes this, why, and how to help

I am Marco Fioretti, tech writer and aspiring polymath doing human-digital research and popularization.

I do it because YOUR civil rights and the quality of YOUR life depend every year more on how software is used AROUND you.

To this end, I have already shared more than a million words on this blog, without any paywall or user tracking, and am sharing the next million through a newsletter, also without any paywall.

The more direct support I get, the more I can continue to inform for free parents, teachers, decision makers, and everybody else who should know more stuff like this. You can support me with paid subscriptions to my newsletter, donations via PayPal (mfioretti@nexaima.net) or LiberaPay, or in any of the other ways listed here.THANKS for your support!