What to do: Political support for Open Data, part 2

(this page is part of my Open Data, Open Society report. Please follow that link to reach the introduction and Table of Content, but don’t forget to check the notes to readers!)

In any case, government officials should be required to justify why any public data should not be freely available to the taxpayers who paid for its creation (taking into account what already exposed in this report, like the fact that charging for PSI to sustain the specific administration that creates them is almost always the least efficient strategy).

Different laws and regulations at this level are the main reason why some success stories from a certain EU country cannot be immediately replicated in others. As an example, the Webhusets initiative in Denmark relies on the fact that even all building designs and lots of technical information about them and the materials used is considered PSI that must be delivered to the City where a building is, and then be accessible by whoever requests it.

The second thing to do is to mandate law that all the PSI that has been defined as public, that is that can be opened without creating privacy, security or similar issues, be actually opened as soon as possible. In practice, it will be necessary to distinguish between PSI that already exists and PSI that will be created in the future. Data in the first category still are, sometimes, in non-digital formats and in a non clear legal status. Therefore, converting them to open formats and obtaining authorization to their publication are extra efforts that must be taken into account.

Data that must still be generated instead are easier to handle. In that case, laws must make it mandatory to publish all that public PSI online with an open license from the start, also for economical reasons: the final cost of ‘adding openness’ at the end because citizens and private businesses start asking for the data that an administration is forced by law to provide is higher than creating open PSI by default from the very beginning. It is equally necessary to establish the principle that all data of the same type created, with public money, by third parties on behalf of some Public Administration also are public PSI that must also be released with an open license. Only under such conditions private businesses and volunteer groups will be able to add value to the data at the lowest possible costs.

As we already mentioned, the advantages of mandating data openness are very easy to see both with strictly technical information like digital maps and in cases like the YourNextMP initiative in UK: all the basic work they are currently doing to collect and digitize candidate data is something that law should oblige each candidate to do by him or herself, without wasting public money or anybody’s time. Every candidate should publish under an open license a full CV using technologies as RDF (Resource Description Framework) that allow to link the data, that is to declare their relationship with other data like unique codes in the companies databases, land or house ownership registries and so on. Once that is granted, services like YourNextMP could finally concentrate on adding value, maintaining simpler Web services that can immediately answer questions like: What companies has this candidate been director of? What charities does he or she support?

The choice of proper licenses for PSI is obviously essential. Common guidelines and recommendations on this topic at EU or at least country level would make much easier to exchange, correlate and reuse PSI, especially because the best choice also depends on the technical nature of the data. When it comes to databases, for example, several experts suggest to not use the popular Creative Commons licenses (with the exception of the one called CC0), but to adopt the Open Database License. The reasons are explained in detail in the article Why Need For Database License and in the Open Knowledge Definition, which comprises 11 clauses providing detail around the core premise that ‘open' data should be freely available online for use and re-use. The UK PSI License is one useful example of the ways in which these generic principles may be practically implemented by governments. The already mentioned LAPSI project will look at all the legal issues related to PSI in much more detail than it would be possible in this report, so we invite readers to follow that project for in depth analysis and legal advice.

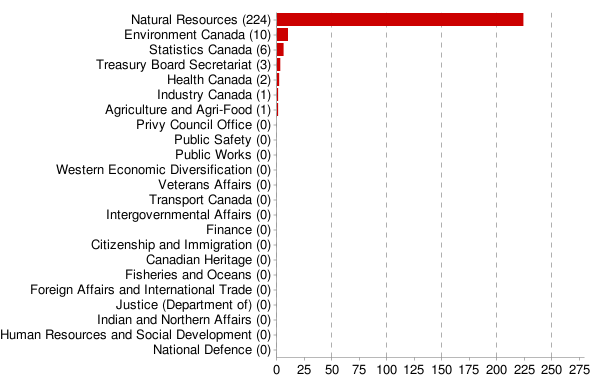

The last category of actions that should be promoted at all levels, but starting from the top, is to create incentives and public demand to open public PSI without waiting for laws that mandate it and/or expose those public bodies that don’t do it. An example of this kind is the website Who’s sharing in Canada? which, in order to “encourage our government to share more structured data, publishes a graph showing which ministries share and which do not. It is a powerful metric of how transparent a given ministry is”.

The UK Councils Open Data Scoreboard does a similar job: as of July 2010 it reports that 18 out of 434 local authorities publish open data (but only 9 are are truly open). The same thing happens in California, where CityGoRound reports in the same period that 691 transit agencies do not provide yet open data to software developers. Another good example from this point of view, still from the USA, is the Public Transit Openness Index, which measures how much Public Transit companies across the USA are open to reuse of their data by publishing lots of parameters, from the file formats they use to whether or not they have sent cease-or-desist letters to third parties reusing their data.

Who writes this, why, and how to help

I am Marco Fioretti, tech writer and aspiring polymath doing human-digital research and popularization.

I do it because YOUR civil rights and the quality of YOUR life depend every year more on how software is used AROUND you.

To this end, I have already shared more than a million words on this blog, without any paywall or user tracking, and am sharing the next million through a newsletter, also without any paywall.

The more direct support I get, the more I can continue to inform for free parents, teachers, decision makers, and everybody else who should know more stuff like this. You can support me with paid subscriptions to my newsletter, donations via PayPal (mfioretti@nexaima.net) or LiberaPay, or in any of the other ways listed here.THANKS for your support!