A quick portrait of digital gerrymandering

Why TODAY? Well, why NOT?

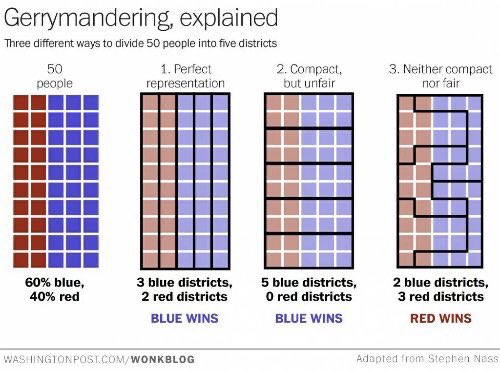

Gerrymandering is (Merriam-Webster) the practice of “dividing or arranging a territorial unit into election districts in a way that gives one political party an unfair advantage in elections”:

Gerrymandering is what, in the recent past, made a party that had “won the national vote by more than 12 percent to earn a one-seat [only] majority” in the USA Congress.

Gerrymandering is a major problem in the United States, but it can happen, and very likely to some extent it does, in every country that holds elections.

Today, gerrymandering is an even greater concern than before, because digital technologies can bring it to a whole new level, in two main ways: by filtering what voters see before voting, and by automatically finding the most convenient way to group them.

Now you see it, now he doesn’t

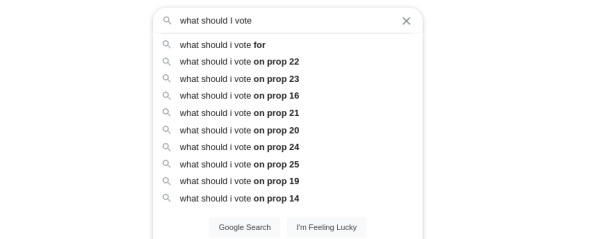

The Google autocomplete function suggests different results to different people, depending on their location, browsing history, and God knows what else. The same applies to actual search results, with Google or any other search engine.

Since most people never go past the first screenful of search results, it is evident that the way in which both autocomplete and results ordering are configured by human beings can hide or highlight information that consistently paints one political party better (or worst) than the others.

A few years ago, a study (see sources below) indeed found that people whose search queries resulted in one candidate’s web pages near the top were more likely to choose that candidate; those who saw a more balanced mix of links were more evenly divided. A similar test with real elections in India yeld similar outcomes.

Facebook and similar social media can be even worst. Last year I noted that “Gerrymandering 2.0 is built right into your social networks”.

In any cases, the social media of today are great, by design, at creating filter bubbles and echo chambers in which people only receive confirmations of what they already wanted to believe, no matter how far from reality it is.

But “digital gerrymandering” can happen by showing more than selected content: “In 2010, Facebook decided to encourage voting in midterm congressional elections by including reminders in some users' feeds, a button to click once they had voted and information about whether their friends had already done so. The social media giant calculated that its intervention accounted for 60,000 votes overall”.

The key word here is some. Who opaquely decided who those “some” would be is the same organization that already knew much more of all its users than we like to admit, including their political preferences.

Twenty years ago, George W. Bush became president of the United States by winning Florida’s electoral votes by a margin of only 537. 60K votes is much, much more than the victory margin needed in many elections these days, in the USA and elsewhere.

Digital map and census analysis

The other method of digital gerrymandering is just the software-turbocharged version of the traditional one: finding automatically, that is via automatic analysis of census data inserted in digital Geographic Information Systems (GIS). With this combination, it becomes very easy to find the way to draw the borders of all voting districts, that maximixes the probability that the “unwanted” voters never are the majority, in any of them.

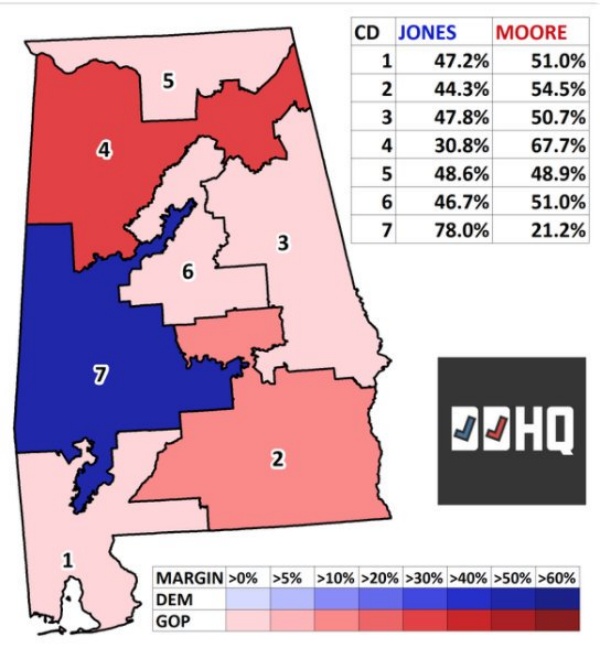

This diagram, about the Alabama Senate elections of 2017, shows what we are talking about:

Do those crooked, highly intertwined borders look anything remotely like the borders of homogenous human communities would come to be, in a state with a maximum elevation of… 730 meters?

The power and precision of combining GIS with Census has been called “the nuclear option for geopolitical mapping analysts….[The capability exists for designing districts by race, ethnicity, gender, political affiliation, demographics, party registration, voter turnout, previous election behavior, and so forth”.

Conclusion/ what to do

Digital or not, gerrymandering is not omnipotent. Total elimination of gerrymandering, in the literal sense, is impossible, if nothing else because voters die, relocate or come of age in more or less random measures between the definition of districts and elections. Minimizing gerrymandering is possible and overdue, but any viable solution must include, as a minimum:

- “the proposition that elected officials are forever prevented from determining their own constituents”

- “serious software development in two key areas: the ability to recognize the gerrymander, and the ability to redistrict without the gerrymander”

- (by me) the most important: voting candidates that commit to find and eliminate gerrymandering

Sources:

Who writes this, why, and how to help

I am Marco Fioretti, tech writer and aspiring polymath doing human-digital research and popularization.

I do it because YOUR civil rights and the quality of YOUR life depend every year more on how software is used AROUND you.

To this end, I have already shared more than a million words on this blog, without any paywall or user tracking, and am sharing the next million through a newsletter, also without any paywall.

The more direct support I get, the more I can continue to inform for free parents, teachers, decision makers, and everybody else who should know more stuff like this. You can support me with paid subscriptions to my newsletter, donations via PayPal (mfioretti@nexaima.net) or LiberaPay, or in any of the other ways listed here.THANKS for your support!