The silent change in the nature of design

Who are designers? Are they ALWAYS designers?

During these months of COVID19 lockdowns, hospitals and healthcare systems have been overwhelmed by (among other things) lack of equipment, or even spare parts for respirators and other machines. Enrico Bassi, coordinator of the fablab and open research hub called OpenDot, in Milan, has just published a nice overview (in Italian) of the efforts to solve this problem, made by the international maker community.

The last paragraphs of Bassi’s piece are interesting well beyond COVID19, because they are about one general transformation happening in society, that is enabled by digital DIY.

What COVID19 has brought to light…

What Covid-19 has brought to light could expand to other areas, becoming a partial, but permanent alternative to design and production as we have seen it so far.

Some might say “this has nothing to do with design or designers”, but it depends. What do you think the designer’s work is?

Personally, I believe that in recent years there has been a silent, but very important change that has transformed design into something more similar to the study of the English language than to mechanical engineering.

Those who translate from English are just a small percentage of all the people who have studied and speak English perfectly. All others use English as a tool to do better something else.

Journalists, voice actors, tourist guides, researchers, etc., all benefit from, or access or produce “content” just thanks to their knowledge of the English language. But translation is not their “core business”, not even remotely.

And this is the point: if you want to be “professional translators” of design, that is designers who collaborate with companies to design and produce new industrial products, this change is of little interest to you.

In the worst case, this change may reduce the size of some markets over time, due to changed consumer preferences.

If, on the other hand, the most precious thing you gained from your work as a designer is the ability to find creative solutions to complex problems, matching aesthetics with technique, and production with usability, then there is a lot to do and change out there.

The communities and projects I (Bassi) presented in my article are the contribution of design experts: people who know about ergonomics, usability, information architecture; people who have read Mari and Norman; people who bring to the table beauty, elegance, efficiency, creativity and pleasure, even when the production tools are still immature.

Those experts are people who understand that they need to collaborate and know how to make the people they work with collaborate as best as possible, even if this means not being the only one to sign the project.

Even if it means designing a process rather than an object. Or, perhaps, the next global response to an unexpected problem.

Ask me how I knew…

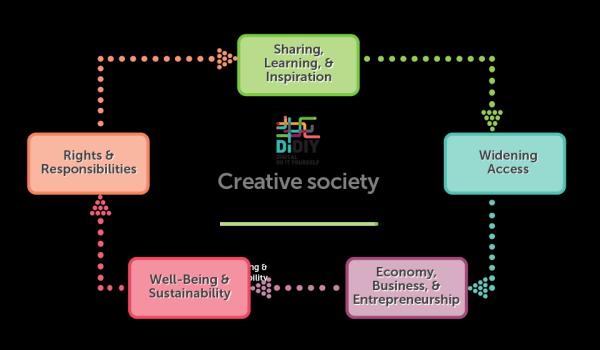

What Bassi says is to me something I already knew… because I was a member of the Digital DIY Project (DiDIY) that researched just this kind of long-term social transformation, and personally have not stopped to do the same. What Bassi writes is, besides being right in itself, of course, also a confirmation of our conclusions, and obviously I am very happy about that. To see what I mean, just compare what Bassi says with the Digital DIY Manifesto for a creative society:

or with the guidelines in the DiDIY Manual.

(This post was drafted in June 2020, but only put online in August, because… my coronavirus reports, of course)

Who writes this, why, and how to help

I am Marco Fioretti, tech writer and aspiring polymath doing human-digital research and popularization.

I do it because YOUR civil rights and the quality of YOUR life depend every year more on how software is used AROUND you.

To this end, I have already shared more than a million words on this blog, without any paywall or user tracking, and am sharing the next million through a newsletter, also without any paywall.

The more direct support I get, the more I can continue to inform for free parents, teachers, decision makers, and everybody else who should know more stuff like this. You can support me with paid subscriptions to my newsletter, donations via PayPal (mfioretti@nexaima.net) or LiberaPay, or in any of the other ways listed here.THANKS for your support!