The problem of crowdwork remains the crowd

You know: those boring humans, so full of needs…

Around 2017, demand for microtasking crowdwork changed quickly and significantly, both in quantity and quality. Florian Alexander Schmidt tried to figure out, among other things, whether this was “a short-lived phenomenon or [something offering] long-term economic prospects for crowdworkers”. This post is my own summary of the resulting report, titled “Crowdsourced Production of AI Training Data” and published in February 2019.

Background: “artificial” intelligence for “self-” driving cars

What caused the sudden change in the demand for microtasking crowdwork was the equally sudden need of lots of high quality training data for autonomous vehicles.

Those data are fed to the so-called self-learning algorithms that “drive” self-driving cars. But their production requires huge amounts of manual labour in data annotation, which is performed by crowdworkers across the globe.

New platforms

To fill this new need, both existing crowdwork online platforms, and new ones created just to answer it, started offering “AI-training data production” as a service.

Since the term “crowd” has negative connotations of cheap labour and low quality results, almost all these services have two, very distinct (corporate) identities: one, that is all about “artificial intelligence” and almost does not mention “crowds”, faces the clients on its own website. The other, with a different online platform, hires and coordinates workers, promising them easy money through microtasks.

More or less work? Both

In this sector, humans and AI work together and train each other. Manual labour trains the AI models, while at the same time similar algorithms are used to support the manual labour and make it more reliable and cost efficient.

Demand for this type of labour will continue to grow rapidly in the foreseeable future: the growth of AI increases the demand for manual labour, which in turn increases the demand for AI automation.

New constraints and responsibilities

The corporate clients of the platforms do not have direct access to the workers (nor they would like it, of course). At the same time, the work is not given to a random, anonymous and potentially incompetent mass, but to handpicked groups of experts that are trained and monitored constantly.

This means that the new platforms could be sued for misclassification of their workers as independent contractors. But, and this is even more important, the same platforms become responsible for the results of the crowd.

Even the workers have more commitments, because they get qualitative and quantitative feedback on how well they do. For them, switching to a new platform means losing the corresponding reputation, qualifications, and skils, at least to some extent. As far as payments are concerned, however, it is much safer and easier to only deal with platform providers.

Business as usual: same old race to the bottom

At the global level, all this activity is based on digital labour that can “flow” dynamically to whoever is willing, for whatever reason, to accept the lowest remuneration at any given time.

Crowdworking platforms can mobilise and dismiss workers at volumes and speeds orders of magnitude higher than what location-based, “physical” services could do. All they have to do is make the work available in a language spoken by a lot of underemployed people with internet access.

The unsurprising result is that the average hourly wage paid out by the platforms apparently levels out globally, like in a system of communicating vessels.

The study describes a perfect example of this situation: Venezuela, and its well-connected, well-educated middle class. Those people fell into hardship all together, due to the economic collapse of the national oil industry. So they became online “migrant workers”, roaming between different platforms without having to - or being able to - leave their country, for whatever pay they could get.

The global village of precarious workers

If the output of crowdwork can be produced independently of the cultural background of the workers, as is the case with e.g. image labelling tasks, providers can get a competitive advantage by accessing workforces from developing nations with substantially lower wage levels.

One case when this does not happen is production of data to train voice assistant software to understand various dialects. In this case, the majority of the work is not exported to developing countries but to those regions where consumers have the greatest purchasing power. In this sector, crowdwork tasks are paid much better, but demand in most languages is too sporadic to make a living from it.

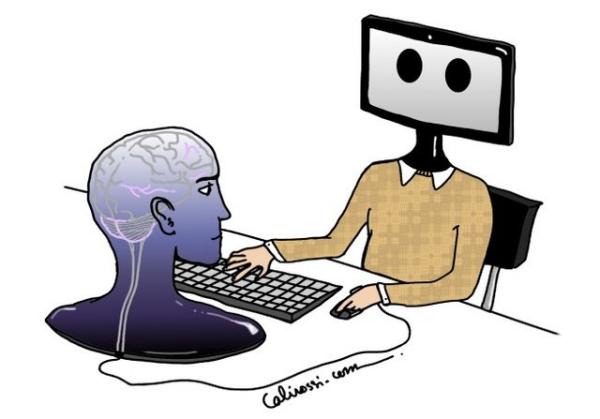

Humans or software? What is the difference?

There are two paradoxes here: one is that current progress in automation is only possible thanks to repetitious manual labour by humans. The other is sometimes on-demand humans, paid just for very short periods, are… cheaper than setting up, or renting, some supercomputer.

At the moment, production of AI training data for the automotive industry demands that, instead of being replaced by the machines, humans are in a complex and precarious relationship with it - by working within it. Humans and AI train and control each other. Within these new systems, the crowd workforce has become a cognitive processing layer within a much larger apparatus, built from layers of artificial and human intelligence. When software replaces workers in some new task, new tasks keep opening up that require human cognitive capabilities. So far.

Conclusion

On the one hand, this system improves some working conditions. Crowdworkers on these platforms can now follow career-paths and are paid regularly and reliably when they work.

On the other hand… a fundamental and potentially unsolvable problems of a global market for crowdwork remain: the race to the bottom in terms of wages, and, maybe even worse, the constant insecurity or precariousness: will there be enough work the next day? Nobody can tell.

Whatever the platforms try to do in the interest of their crowdworkers, those workers cannot have any guarantee that “tomorrow the task they have specialised on will not be automated or performed by someone more desperate”.

The crowd is a mass phenomenon in which the individual human is by definition replaceable. The crowd is the equivalent (Marco: or should we say “the biological side”?]) of the seemingly endless mass of repetitive and interchangeable microtasks that constitute AI training.

As long as it is that easy to access, almost at an instant, crowds that recruit themselves and can be trained and managed automatically, the workforce has hardly any negotiating power with which to improve its wages or working conditions. That is to say: the problem of the crowd remains the crowd.

Image sources: worth-reading articles on the same topic by SmallBusiness Italia, TechXplore, Steemit and Metis

Who writes this, why, and how to help

I am Marco Fioretti, tech writer and aspiring polymath doing human-digital research and popularization.

I do it because YOUR civil rights and the quality of YOUR life depend every year more on how software is used AROUND you.

To this end, I have already shared more than a million words on this blog, without any paywall or user tracking, and am sharing the next million through a newsletter, also without any paywall.

The more direct support I get, the more I can continue to inform for free parents, teachers, decision makers, and everybody else who should know more stuff like this. You can support me with paid subscriptions to my newsletter, donations via PayPal (mfioretti@nexaima.net) or LiberaPay, or in any of the other ways listed here.THANKS for your support!