No broadband? No informed voting, sorry

Education and jobs? What about the process to govern them?

In the USA, as recently as 2013, a Pew found out the Digital Divide to be a ‘major challenge’ in teaching low-income students. One important reason was that, in many rural communities, there was only one public place to study online for students who could not afford broadband, mobile or not: the local McDonald’s and other businesses offering free Wi-Fi.

In addition to teaching, an opinion piece from Nevada explained why “Digital literacy is imperative [also] for America’s economic future”: “possessing these skills is absolutely essential for accessing the jobs and education”.

Aren’t we forgetting something here?

What about politics?

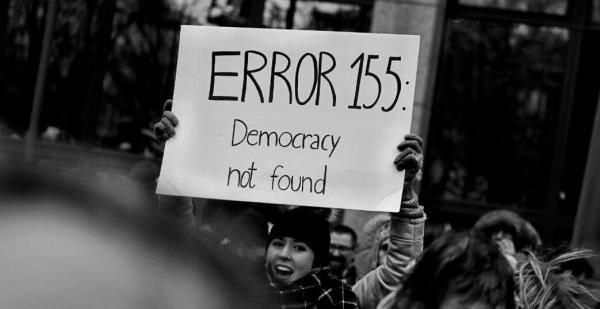

A mandatory requirement for free and fair elections is that as many citizens are possible can present their candidates, access all relevant information and participate to debates.

These days, people who do have access to both broadband internet connectivity and reliable electricity, plus of course the money to pay for such services, can do all the things above online (in theory, of course. In practise, all too often their ability to deliberate is destroyed).

What about the others, tough? Can they still propose their own candidates, stay informed and participate to the political discourse, in this age where politics has already massively moved online? The answer, more often than not, is “no, they are just pushed out of politics”. Here are a couple of examples.

In Mexico, independent presidential candidates must collect 866,000 signatures using a mandatory mobile app that only runs on relatively new smartphones. This means whoever wants to endorse a candidate needs a smartphone costing (in 2018) “around three times the minimum monthly salary”. In addition to reliable electricity and affordable data contracts, of course.

In 2018, these digital barriers “doomed the candidacy” of “Marichuy” Martinez, the first indigenous woman to run for president in Mexico.

Most members of the indigenous communities that Marichuy wanted to represent do not have recent smartphones, reliable electricity and data contracts, so she could not get enough signatures.

In the Philippines, many members of the same groups have to “hike over eleven bridges to the nearest highway”, in order to find a cell phone signal, a 2017 research found. Last but not least, as explained in the second link, those who can’t participate or or choose their own candidates because they lack internet access are “disproportionately poor, female, indigenous and living in rural areas”.

Take home lesson? Basic access to information and communication is not just a matter of money or good grades (which of course are important, and usually the first things to care for): it is a matter of politics.

Who writes this, why, and how to help

I am Marco Fioretti, tech writer and aspiring polymath doing human-digital research and popularization.

I do it because YOUR civil rights and the quality of YOUR life depend every year more on how software is used AROUND you.

To this end, I have already shared more than a million words on this blog, without any paywall or user tracking, and am sharing the next million through a newsletter, also without any paywall.

The more direct support I get, the more I can continue to inform for free parents, teachers, decision makers, and everybody else who should know more stuff like this. You can support me with paid subscriptions to my newsletter, donations via PayPal (mfioretti@nexaima.net) or LiberaPay, or in any of the other ways listed here.THANKS for your support!