A "complex" economy may make all journalists blind

I found a paper about concentration of certain human activities in large cities that… maybe does not give enough coverage to some among the most important of those activities.

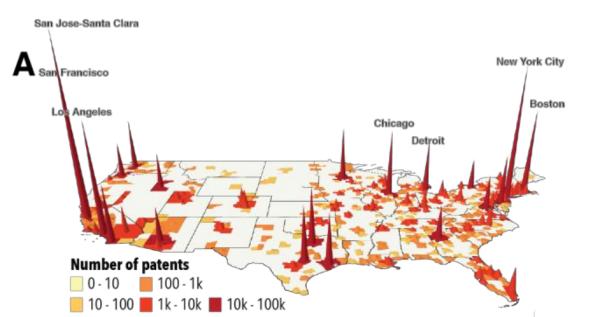

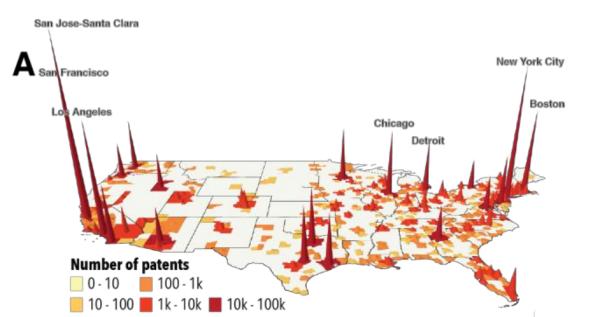

Map of spatial concentration of patents in the USA

</em></u>

The paper titled “Complex Economic Activities Concentrate in Large Cities”:

- presents “evidence that complex economic activities [namely: technologies, scientific publications, industries, and occupations] concentrate more in large cities”

- asks “Why do some economic activities agglomerate more than others? And, why does the agglomeration of some economic activities continue to increase despite recent developments in communication and transportation technologies?”

- suggests that “the increasing urban concentration of jobs and innovation might be a consequence of the growing complexity of the economy”

The chart at the top of this article summarizes one of the sides of the phenomenon. It shows the concentration of patents in a few spots across the USA.

What is interesting, and what I find should have been added to that paper, is how that the peaks in those chart are basically identical, in size and distribution, to the bubbles in this other chart:

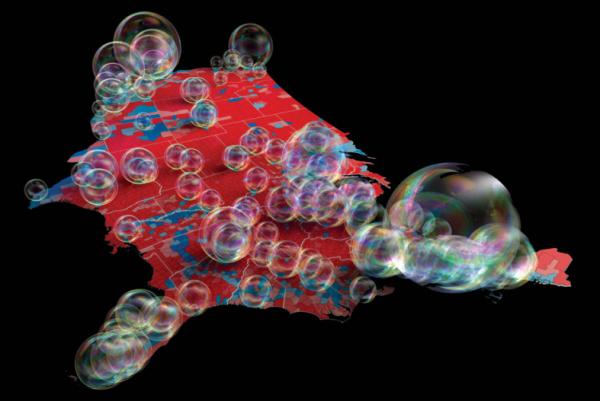

The 150 USA countries with the greatest number of newspapers and online publishing jobs, and how they voted. Compare with the first chart, copied below for your convenience

</em></u>

which comes from “The Media Bubble Is Worse Than You Think”, by Jack Shafer and Tucker Doherty, and is about information and politics. Here is the description of that chart:

“The map… shows how concentrated media jobs have become in the nation’s most Democratic-leaning counties. Counties that voted for Donald Trump in 2016 are in red, and Hillary Clinton counties are in blue, with darker colors signifying higher vote margins. The bubbles represent the 150 counties with the most newspaper and internet publishing jobs. Not only do most of the bubbles fall in blue counties, chiefly on the coasts, but an outright majority of the jobs are in the deepest-blue counties, where Clinton won by 30 points or more”.

The article also quotes the explanations by Nate Silver and Steve Bannon of why, in 2016, USA national media “didn’t get the nation they purportedly cover”:

- Silver: “the ideological clustering in top newsrooms led to groupthink: as of 2013, only 7 percent of [journalists] identified as Republicans”

- Bannon: “The media bubble is… just a circle of people talking to themselves who have no fucking idea what’s going on.”

Shafer and Doherty, however, point out that:

Journalistic groupthink? It is a symptom, not a cause

And this is where, in my opinion, things get really interesting, and a connection with that other paper emerges. Shafer and Doherty describe the map above as “a revelation” because it makes it evident that:

- The national media really does work in a geographical and political bubble, something that wasn’t true as recently as 2008, and that bubble is growing more extreme

- Most working journalists are very likely to reside in one of the nation’s most pro-Clinton counties

Who did it? Economics

Shafer and Doherty go on to explain that the majority of national media jobs concentrated where people vote Clinton because of something “structural, and quite difficult to alter: economics”:

- In late 2015, “for the first time, the number of workers in internet publishing exceeded the number of their newspaper brethren”…

- … but while newspaper jobs are spread nationwide, “almost all the real growth of internet publishing is happening outside the heartland, in just a few urban counties, all places that voted for Clinton”* All else being equal, specialized industries like to cluster.

- Traditional newspapers “must locate next to… people who consume local news, and whom local advertisers need to reach”

- Online media, instead, “has been free to form clusters, piggyback-style, on the industries and government that it covers”.

- The result is a media bubble that “has drifted very far from the average American experience”

- because only Internet media is growing, but it creates jobs only in places that “are dense, blue and right in the bubble”

And here the circle is completed

Shafer and Doherty conclude that “places with money get served better [even by media mirroring/adsorbing their views] than the places without [but] people in big media cities aren’t just more liberal, they’re also richer”.

Adding this to the findings of the other paper, it seems we have have data showing how:

- as the economy gets more complex, it tends to concentrate more in large cities

- so do the people working in complex sectors, that is the people who make more money, have less to fear from globalization, got a better education an so on

- but, thanks to the Internet, those people attract closer and closer to them everybody providing news

- the same closeness unavoidably wraps almost all journalists in a 24x7 bubble made of the same views that the few working in the complex economy hold dear

Alternative wording of the same summary:

- the more (uselessly?) complex the economy becomes

- the more it literally clusters, isolating them from everybody else, physically and then ideologically…

- not only its most privileged and sophisticated protagonists (nothing new, so far, right?)

- but also, will they nill they, all those who should explain to everybody else how society is really doing, and where it may go next

One sentence summary: the more “complex” an economy becomes, the more it lets all media people see and live only the views and experiences of the fewer and fewer who lead that economy.

Question left for readers, or a next post: how much of the “complexity” is technological advancement, and how much financial deregulation, or other “non-tech” policies?

I repeat it: the connection among the theses in that paper and articles definitely deserves more investigation and dissemination. If I can give a hand, just contact me.

Who writes this, why, and how to help

I am Marco Fioretti, tech writer and aspiring polymath doing human-digital research and popularization.

I do it because YOUR civil rights and the quality of YOUR life depend every year more on how software is used AROUND you.

To this end, I have already shared more than a million words on this blog, without any paywall or user tracking, and am sharing the next million through a newsletter, also without any paywall.

The more direct support I get, the more I can continue to inform for free parents, teachers, decision makers, and everybody else who should know more stuff like this. You can support me with paid subscriptions to my newsletter, donations via PayPal (mfioretti@nexaima.net) or LiberaPay, or in any of the other ways listed here.THANKS for your support!