One hour with the XO laptop in a Nepali school

On Nov. 5th, 2009, during the first OLE Assembly in Kathmandu, I visited a class that uses the XO laptop in the Binayak Bal School of Badal Gaun, Nepal.

Nepal is a wonderful country, but it is still a very poor one (470 USD average yearly income). One of the consequences is that, according to Rabi Karmacharya, executive director of OLE Nepal, “even in the third and fourth grades, many children really don’t know how to read”. While I do know about some success stories of computers for primary education, in general I’m skeptical about their effectiveness. Therefore, I was very eager to see what learning with the XO would be like.

I could have assisted to Nepali or English lessons in grade One and Two, or to a Maths lesson in grade Six. Since all lessons are in Nepali I chose the latter, assuming that I could follow much more easily a Maths class than a language one.

The sixth grade class counts about twenty boys and girls. During that Maths lesson the XO was used for only 15/20 minutes, in the middle of the lesson. First, the teacher explained how you go from linear to square and cubic units of measurements with the standard, good old methodology: chalkboard drawings, verbal explanations, frequent questions to the class.

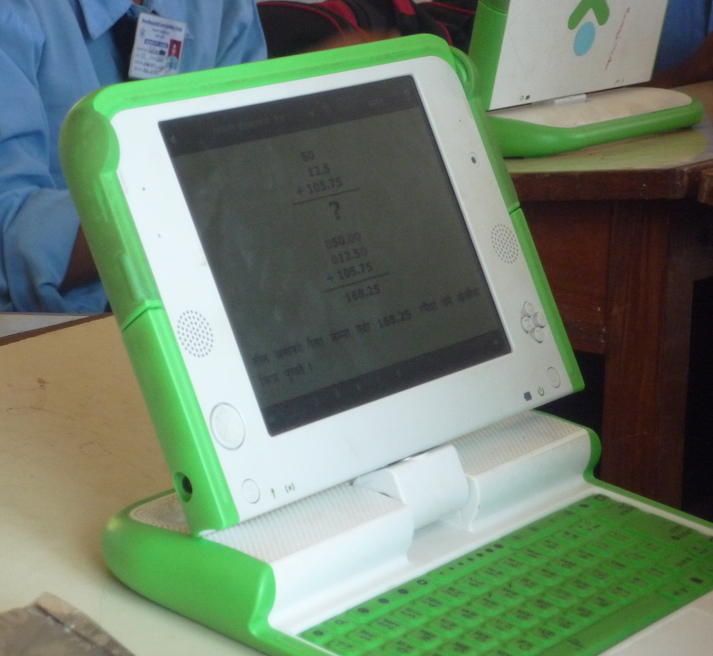

After that, probably as a verification of what had been explained in earlier lessons, all students got their laptops and started to practise with floating point sums. During this phase, the teacher assisted whoever asked for help (almost nobody, actually). The class spent the last ten minutes or so revising floating point sum with the teacher, again using the chalkboard. [

Is it worth it or not?

I can’t certainly draw any general conclusion about XO or any other individual computer in the classroom after one hour. This said, here are my impressions after this experience.

First of all, time: all children must simultaneously get up and take their laptops from the charging rack, wait for them to boot, find and load the right program, turn the computers off and put them back in place. This can waste a not negligible chunk of a 45/60 minutes lesson. In the classroom I visited this time didn’t exceed 6/7 minutes, so it wasn’t really a big deal and it surely decreases with practice, if the teacher keeps everything under control.

Another issue is distraction. One or two kids spent their laptop time doing something else with it, instead of the required math exercises. Whether it was due to not knowing what to do or simply lack of interest, I don’t know, but I’m sure it has nothing to do with the laptop. Students of all ages get distracted every day all over the world, no matter what’s on their desk or how good their teacher is. The only thing that could make a difference is very small classes, but that is often outside the school’s control, isn’t it?

Almost all students did their exercises with great commitment. They mostly worked alone. When needed, they helped each other as they would without laptops, that is without using at all the wireless interface of the XO or any collaborative software.

So why use individual laptops? From the little I’ve seen in Binayak Bal, one of the answers may be “because computers with the right software can greatly help to optimize a low level, repetitive part of teaching, that is to assign and verify exercises”.

During those 15 minutes with the XO laptop, each child was able to practice as much as he or she could handle. Without slowing other students down, without being slowed down by other students and, above all, without wasting on trivial tasks the time of the one teacher available. The teacher was always there and directly helped children who had actual problems. But he could do that better, exactly because he didn’t have to assign and check manually some 50/60 additions first, just to find who needed help most urgently. The computers took care of that.

For all these reasons, my impression so far is that individual computers in primary school may indeed help when (as it happens with the JumPC) they are integrated in the standard curriculum, to support teachers prepared and motivated to use them.

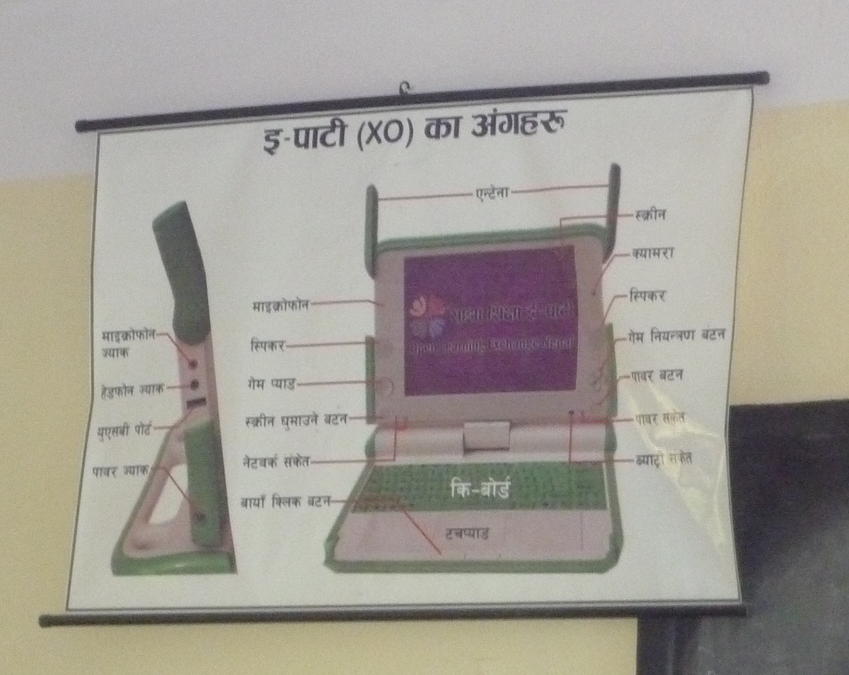

Most involved teachers report that the laptops make them more systematic and effective. This certainly happens because, thanks to OLE Nepal, they not only have a dedicated, 130 pages manual in Nepali, but they all went through several days of full time training before starting school.

Final thoughts on flexibility and commitment

I’ll conclude this small report with three general remarks. The first is that, in order to work as I described there is no need to have just the XO. Any other individual laptop or custom computer with the right software would work just as well.

Next, 100% localized software and content as they are creating in Nepal is absolutely essential. Several Binayak Bal students speak English better than I could say of many Italian children of the same age (hats off to them and their teachers!), but any benefit of using computers in primary education would be enormously reduced by built-in language barriers.

I’ll end with another compliment to the students which has little to do with laptops. It is all too easy for Western teachers to get students who behave like they’re doing you a favour to just show up. The children at Binayak Bal, instead, gave me the impression that they’re aware of how lucky they are to get a good education, and intentioned to make the best of it. Maybe these are the differences, rather than those between teaching with or without laptops, to which we should think about first.

Who writes this, why, and how to help

I am Marco Fioretti, tech writer and aspiring polymath doing human-digital research and popularization.

I do it because YOUR civil rights and the quality of YOUR life depend every year more on how software is used AROUND you.

To this end, I have already shared more than a million words on this blog, without any paywall or user tracking, and am sharing the next million through a newsletter, also without any paywall.

The more direct support I get, the more I can continue to inform for free parents, teachers, decision makers, and everybody else who should know more stuff like this. You can support me with paid subscriptions to my newsletter, donations via PayPal (mfioretti@nexaima.net) or LiberaPay, or in any of the other ways listed here.THANKS for your support!